Auction Insights

Signatures from 16th & 17th Century England

What does your name signify? When writing your signature whether on a birthday card or a legal document does it any longer carry ‘weight’, a certifying of your authenticity in the contactless age?

Biometric technology and the increasing use of artificial intelligence will only make the days when writing a cheque, letter or licking a stamp seem as outmoded as riding a Penny Farthing bicycle. But consider how you would feel were someone else to imitate or forge your signature. Feelings of bewilderment, embarrassment and anger are some of the emotions which you would not feel were to suffer the loss of, for example, a bunch of keys or the theft a small amount of money.

One reason people feel so strongly about their signature can be explained by graphologists who believe much can be read into a person’s character from their handwriting.

The signatures of eminent figures, both living and long dead, can be valuable to collectors especially if they believe it possible to read into them more than just that which is apparent on a page.

Of all the oddities that turned up at a recent Saturday valuation morning at Mellors & Kirk none were as exciting as a very battered small leather bound book that was literally dropping apart.

It was not a book in the traditional sense but an autograph album of signatures of the great, mostly very great, but not always the good, from 16th and 17th century England. Mostly clipped from the ends of letters or documents the small slips of paper were stuck onto individual pages perhaps 200 years ago. The whole lot could make up to £10,000 when it goes to auction in Mellors & Kirk’s Fine Books and Autographs Sale in April.

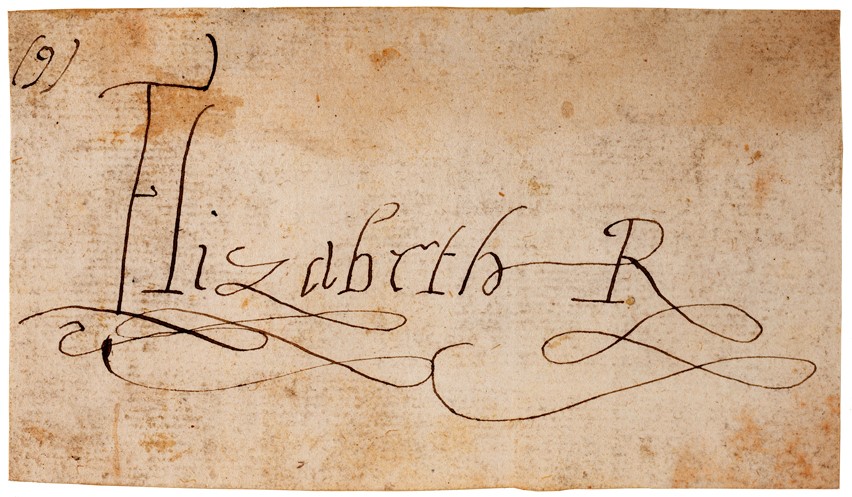

Queen Elizabeth I was so great that she was known by the alternative name Gloriana. Her signature – shown here actual size – and no doubt cut from the head of a letter (only us lesser mortals sign a letter at the end) must have taken ages to write, it is so elaborate. The main part of the letter would have been written by one of her secretaries. Such letters or documents would correctly be described as being not signed or autographed but written “under the Queen’s sign manual” which means that the name was actually handwritten by the monarch herself.

Hers is perhaps the most beautiful of any King or Queen’s signature. As anyone who has visited Hardwick Hall will know, the magnificence of the ‘Virgin Queen’s’ court, the precarious throne she inherited and her personal qualities, not least in defeating the Spanish Armada have assured for her a unique status, as both monarch and woman. Her signature is estimated to sell for £800-1,200, a lot for so small a piece of paper but cheaper by far than many postage stamps. Possibly even more valuable will be the signature of her half-sister and predecessor ‘Bloody Queen Mary’ (1516-1558). She leaves one in no doubt who she is, signing ‘Marye the quene’.

Rarer by far is Bishop Hugh Latimer’s signature. It is not every day I get my hands on something written by a genuine martyr, yet here it is, on the very next page to ‘Bloody’ Queen Mary whose regime condemned him, Matthew Ridley and Archbishop Thomas Cranmer (who was born at Aslockton) to be burned at the stake in Oxford in March 1556. Latimer’s last words were “We shall this day light such a candle by God’s grace in England as I trust shall never be put out”. It is a wonderfully inspiring tiny memento of a great Englishman.

Queen Elizabeth I in perhaps her second most famous quotation remarked that she had “no desire to make windows into men’s souls”, but that didn’t stop her setting great store by the advice of her brilliant spymaster William Cecil 1st Lord Burghley (1520-1598) who was at her side for most of her long reign. The example of his signature is particularly strong and bold. Burghley’s home, Burghley House near Stamford is one of the pre-eminent examples of Elizabethan architecture.

Someone else who was at her side in a quite different way was Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex (1565-1601). Theirs was one of the greatest and tempestuous of royal love affairs in history. A politician on the make, he charmed Elizabeth who rewarded him in a cat and mouse relationship which ended in his execution.

Brave and witty, he both underestimated Elizabeth on account of her being a woman and shocked other courtiers by the degree to which he overstepped the mark. His is yet another signature that has lain in this little book with its ill-matched bedfellows since the 18th century.

Finally the album revealed another 16th century surprise in the signature of Lord Hunsdon (1526-1596). If his isn’t a household name that of his protégé certainly is, William Shakespeare.

Hunsdon was the patron of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, Shakespeare’s own company of actors for which the plays were written, including, in the year of Hunsdon’s death, Romeo and Juliet.

His therefore is the signature of a man about whom, short of Shakespeare himself, it can safely be said (with apologies to Sir Winston Churchill) ‘Never in the history of literature was so much owned by so many to one man’.

What better way to leave this brief excursion into Elizabethan England, and answer my initial question than by a famously beautiful line from Romeo and Juliet “What’s in a name? That which we call a rose/by any other name will smell as sweet”.

< Back to Auction Insights